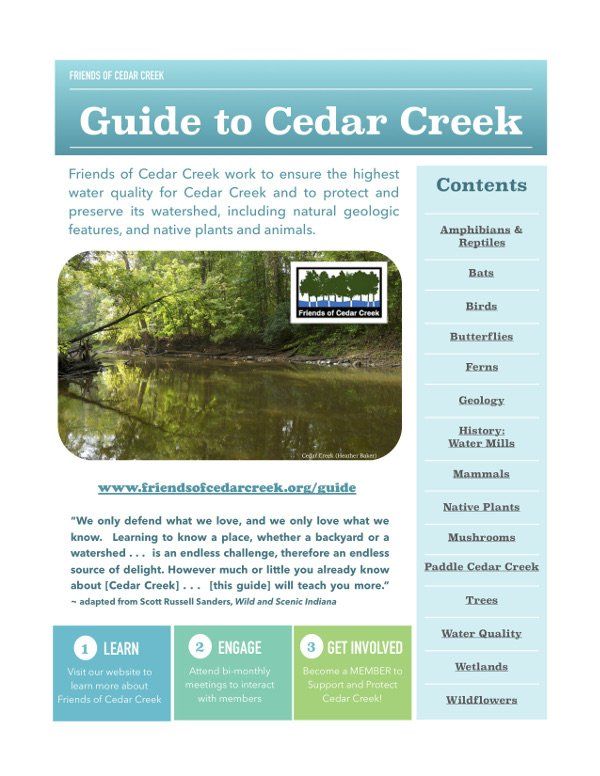

Guide to Cedar Creek

Turtles, Snakes and Salamanders ... Oh My!Dr. Bruce Kingsbury

A snake? Or what is it? Is it venomous? When you live in a place like Cedar Creek, you don’t know what is going to come out of the woods. But that is part of the area’s charm. In fact, there are no venomous reptiles in the area. So the mystery should no longer be one of determining risk, but of satisfying one’s curiosity about a marvel of nature.

Cedar Creek Corridor - the stream, forests and other natural habitats - is one of the finest natural landscape corridors in northern Indiana. This means not only more trees, flowers and deer, but also a wider array of critters, including reptiles and amphibians ranging from toads to salamanders, turtles, and snakes.

There are a number of reasons why Cedar Creek has such diversity, beginning with the area’s variety of habitats suitable for these animals. As described below, different species have varying habitat requirements, and the watershed has enough of these to be home to many species. The sheer size of the natural landscape also means that many species lost in other areas persist along Cedar Creek. Just as grizzly bears need more room than Yellowstone National Park, Eastern Box Turtle populations need something as large as Cedar Creek to persevere.

So what all do we have? Are any dangerous to us or to our pets? I present here a brief review of the more common, and a few of the unusual reptiles and amphibians of the Cedar Creek watershed. I hope reading this will both inform (and perhaps relieve) you.

That there are no venomous snakes in the area may come as a surprise. There is only one species of venomous snake in northern Indiana, the Massasauga, a small rattlesnake usually found in marshy areas where most people would never go. They are rare, so it is hard even for experts like me to find them. And those cottonmouths? The truth is that they have never been reliably observed anywhere but in southernmost Indiana (they may no longer occur anywhere in the state). Instead, folks are likely seeing Northern Watersnakes which are ubiquitous wherever there is water. Neither venomous nor otherwise dangerous, they are not aggressive--unless you try to pick them up--then they will bite!

The most likely snake encounters will be with Eastern Gartersnakes and Eastern Ribbonsnakes, generally easy to identify right away as both species usually are striped from head to tail. The Ribbonsnakes are quite slender with chocolate brown rather than white stripes on the sides of their bodies. Perhaps the most common snakes in the watershed are the Brownsnakes. These little cuties are only about eight inches and very secretive, so even though they can be pretty abundant in the forest, you may not see them.

Since Cedar Creek corridor is one of the finest natural landscape corridors in northern Indiana, it can support several species that you might not see in many other areas. Two big snakes are the Racer and Ratsnake. Both species can exceed four feet, perhaps five in northeastern Indiana. In southern Indiana racers are black, but become blue further north. Around here racers are taking on the blue tint, so you will hear about Blue Racers. The Ratsnakes have more of a dark gray overall color and a subtle salt and pepper chain pattern (that you won’t see until you are close enough to be a little nervous). Ratsnakes are good climbers and probably have surprised those who have discovered them in the rafters. On the plus side, since they are in the rafters to find rodents, they are helping you with pest control. You’re welcome.

The Box Turtle is a handsome turtle found wandering about in the forest as it searches for berries, earthworms - and other box turtles. The species is increasingly rare across their range, but a few remain along Cedar Creek. They need large healthy forests to persist, and, since a lot of people think they are more adorable than snakes, many are collected as pets--which is illegal in Indiana. Why? Because box turtle populations are so small, such collecting (even by herpetologist wannabes) tips their populations towards extinction.

The more common Snapping Turtles and Painted Turtles may be seen basking on logs in the creek and associated wetlands, or they may show up on the road or in your gardens and yards, especially in spring. What are they doing there? They are likely females looking for a place to lay their eggs! Once finished, they will head back to the water. If you find a turtle on the road, consider helping it across. When cars go by, the turtles “freeze” in place, making them vulnerable to getting struck. Some of us will just pick them up and move them, but moving a big Snapping Turtle is a bit more problematic. Shoving them along the road with a broom is an interesting activity. They will protest. But you are doing them a favor.

Believe it or not, the most abundant vertebrates in the Cedar Creek watershed are likely salamanders! Throughout the forest are Redbacked Salamanders, only about two inches long, living in the leaves and under logs and other woody materials on the forest floor. These animals are interesting in several ways. They are called “lungless” salamanders because, in fact, they are lungless, relying entirely on the skin for gas exchange. They are also of interest because instead of relying on wetlands to breed, they lay eggs in moist locations in the woods, such as inside logs.

All of the other species of salamander in the area are likely “mole salamanders” of one kind or other. These species are called mole salamanders because they spend most of their time underground, visiting wetlands only in late winter and early spring to breed. More common species in the area include Smallmouthed and Tiger Salamanders. Smallmouths are more abundant in the woods, Tigers in the fields. Both rely on shallow, often temporary, wetlands rather than the Cedar Creek itself. They may be encountered in spring around your home in basement window wells or underneath anything in the yard. These individuals are either going to--or leaving--wetlands and have run into a hazard along the way.

Although the prominent aquatic feature in the watershed landscape is, of course, Cedar Creek, it is important to note that to most amphibians and reptiles, the wetlands nearby are more critical than the creek itself. Often called ephemeral wetlands because they may hold water for only part of the year, these water bodies are critical breeding sites for most salamanders and frogs in the area. Fish are effective predators of most amphibian eggs and larvae, and ephemeral wetlands are fish-free.

By the way, these wetlands are not mosquito factories. Mosquito densities are lower around healthy wetlands because of the abundance of predators there. And to digress further, it turns out that the mosquito species in these habitats are not the ones that tend to carry human disease. Instead, human-disease-carrying species frequent human habitations and breed in faulty gutters, trash and other preventable hatcheries. Score one for wetlands!

The two frogs that Cedar Creek residents are most likely to encounter are the Eastern Gray Treefrog and American Toad. Because treefrogs do spend a lot of time in trees, you may hear their bird-like trills coming from above through much of the year. Otherwise, it is not unusual to find them in nooks and crannies around the house such as under siding edges, or tucked in gutters, as they await evening to come out and hunt for bugs. They may be gray or green with a bold or subtle background pattern. Curiously, the same individual may change color over the day, including how strong any patterning appears. This has more to do with temperature and mood than background color. Regardless, around here, they are all the same species.

Toads take a different approach. They are ground dwellers, perfectly content to hang around the house helping you with bugs, so long as things are not too dry. Although they don’t need standing water like many frogs, they do need moist refugia. You can encourage them by making toad “houses” such as crawl spaces in stone walls, and large garden stones with gaps beneath. In such closed space the toads can rehydrate before they wander out again to eat more bugs.

Ultimately, most people who move out to a place like Cedar Creek move there to get out in the country, and into nature. Things that slither are part of that, and now that you know a little more about our amphibians and reptiles, and that nothing venomous lurks out there, I hope you will welcome these unique critters into your yards!

If you ever have any questions about reptiles or amphibians, please don’t hesitate to ask me. Happy to identify those mysterious creatures in photos, regardless of critter type. Just send them to me at

bruce.kingsbury@ipfw.edu. And consider joining the Environmental Resources Center at

http://erc.ipfw.edu and signing up for our newsletter. Thanks!

More to Explore . . .

- Bruce Kingsbury is Professor of Biology, Director of the PFW Environmental Resources Center, and Associate Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Purdue University Fort Wayne (PFW).

- The new Indiana Herpetology Atlas

has range maps for counties, and photos of each species and their ideal habitat so you can learn about them and figure out what you have seen.

Amphibians and Reptiles Image Information

Northern Water Snake

(Dr. Bruce Kingsbury)

Black Rat Snake

(Dr. Bruce Kingsbury)

Eastern Box Turtle

(Heather Baker)